Knots that are us: psychosis and the family

by Timothy

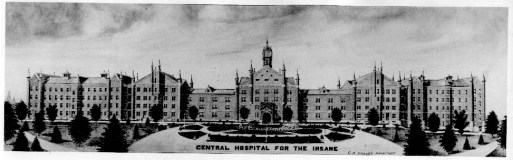

My earliest memory of a state mental institution was when I was seven. I was visiting my mother at Central State Hospital in Nashville Tennessee. It was a frightening and chaotic place that remains a part of the landscape of my childhood memories.

I visited my mother there throughout my childhood, but was never quite equipped to grasp the struggles in the faces of custodial patients who wondered the grounds or the halls of the neglected asylum buildings, in spite of those struggles nevertheless being all too visible to me.

This was equally true of my mother’s face, her struggles.

When I was 12 she went into Central State for what would become a long time. I would go on to stay with other family members, and then a foster home. But when I was nineteen I found myself living with my mother once again. By then I’d been struggling with my own psychosis for a number of years. I’d lose jobs when my often confusing and difficult thoughts would lead to equally confusing and difficult behavior, and I wasn’t much able to pay rent anywhere. In the midst of an acute episode I moved onto my mother’s couch in a government housing project in Nashville and applied for Social Security Disability benefits. This was a dark chapter of my life.

****

I talk about my mother quite a lot, and in some ways maybe that’s problematic. But when I talk about my mother, it’s not her I’m really talking about. I’m talking about myself. I’m talking about my relationship with her, my experience of her experience. These profoundly structure how I think about what society, and she herself, calls mental illness. Both my experiences with her growing up, and then later the confusion between my own madness and hers, these structured in many ways my struggle to recover the meaning in my own experiences.

I am a family member of a person who experiences what she calls “severe mental illness.” What’s more, my mother is a mother to a son who experiences psychosis.

A recent essay on Pacific Standard, a piece from the always careful and insightful Nev Jones, and a post from Lisa Long—all grapple in distinctive ways with the experience of being a family member of a struggling person. The juxtapositions of these pieces alongside recent reflections about my own family experience inspired this post.

There have been and remain frequent tensions between those who advocate from the position of family member versus those who speak as service users or survivors. The historical context of these tensions is quite complicated, and beyond my present scope.

Suffice to say, though on the surface the arguments are often around issues like compulsory treatment, guardianship, and medication, all crucially important issues—it is vital to recognize the extent to which affectively charged and deeply moral concerns permeate these issues. These are bound up in responsibility, agency, familial obligation, parental duty, love,—all these ties which not only bind us but which constitute us, are us—these entangled stakes in which we feel our way along and do the best that we can.

****

The frequent polarization between family advocates and service user/survivor advocates is both painful to witness up close, but I believe also leads to positions on “both” sides that often seem more reactionary than a thoughtful accounting of the often extremely difficult dilemmas in the messiness of actual lives. It also sets up a false dichotomy between “them” and “us,” particularly so when we consider that so many of them are also us.

As a service user and survivor, a mad person, I’d like to see less reliance on notions like self-determination and individual responsibility—concepts not above scrutiny— and think a bit more about interdependence and collective responsibility. These are old ideas going back millennia and emerging in family and narrative therapy traditions from which they’ve been borrowed by promising approaches that seem quite popular among many survivors like Open Dialogue and Intentional Peer Support, principles also built in to rigorously evaluated and more mainstream services like those for first episode psychosis.

As a family member, I’d like to see a space open up where we develop responses outside what sometimes seems a forced choice between coercion and over-involvement on the one hand, and abandonment on the other. Where programs that can skillfully assist us in negotiating our sense of duty to look after the well-being of our loved ones, while also committing ourselves to the discernment and support of their agency.

I’d like these programs to be widely available and accessible. I’d like them to be informed by the best evidence that we have while recognizing that there are limits to what conventional scientific methods can tell us. The meanings of these experiences are constructed and re-constructed in the context of actual lives and are thus profoundly social, cultural, and experiential.

At the same time it also seems quite obvious that the body and the lived experience mutually entail each other, are co-extensive as Daniel Siegel has characterized it. Its a false choice between colloquial Cartesianism and biological reductionism. There is room for the body, the brain, the lived experience, the family, the social, the cultural, and the spiritual.

****

Today my mom is living happily on her own. She’s had a partner for years who she likes very much and who treats her well. She’s involved in advocacy efforts to improve conditions for impoverished people with psychosocial disabilities. Just last month I spent several hours on the phone doing my best to tutor her in statistics, one of her last classes she needs to finish her bachelor’s degree, a goal she’s had for decades. At the same time I was struggling through the last of my own statistics courses for my PhD. Sometimes we joke to each other about her “thought broadcasting,” or my “paranoia,” but these things are more textures in our lives and much less a hindrance to our fashioning these lives in accordance with our own vision and our own capacities. I’m not so much a fan of the term “recovery.” But if it’s anything, that’s it.

Here’s a short video of me playing original music on the piano with my mother in 2008.

Mr. Kelly Piano from Veronica Rose on Vimeo.

The Families Healing Together looks like a very promising resource for families.